[Guest post by Timo Luege - I’m passionate about information, communication and how they can be used to make the world a better place.

My two main areas of expertise are:

• Communication through digital media

• Media relations during disasters

Over the last thirteen years I have worked for the Red Cross Red Crescent Movement, the UN, German national public radio and a wire agency Social Media 4 Good] on June 29 -

On June 1st, USAID launched its first ever crowdsourcing project. Yesterday, they shared their lessons learned during a webcast, in a power-point and a case study. Here are the main takeaways.

The USAID project was a little different from what many people have in mind when they think about crowdsourcing; it did not involve Ushahidi, nor did it have anything to do mapping data submitted by beneficiaries. Instead it was a clean-up operation for data that was too messy for algorithms to comprehend.

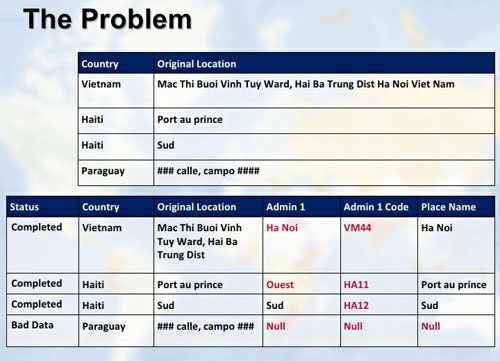

USAID wanted to share the locations of regions around the world where it had made loans available. The problem was that these locations were not captured in a uniform format. Instead, different partners had submitted the information in different formats. In order to show all loans on a map, USAID needed a uniform data structure for all locations.

Combined human-machine approach

Before sharing the data with the volunteers, USAID had already tried to clean the data with scripts. This meant that only the datasets remained, that were too difficult to be treated automatically.

I like that USAID did not simply outsource all the data to the crowd, but used human intelligence only for the cases that were too hard for the algorithm. This demonstrates that human capacity is seen as a valuable resource that should only be requested and used where it can have the highest impact.

Humans more accurate than algorithms

After the project, USAID asked the GISCorps to take a random sample of the machine-generated records as well as the human-generated records and compare their accuracy. According to analysis, the volunteers were more accurate than the machines, even though most volunteers weren’t GIS experts:

While 85 per cent of the records cleaned up by the volunteers were accurate, only 64 per cent of the records treated by the algorithm were correct. The volunteers were also much faster than expected – instead of the predicted three days, it only took the volunteers 16 hours to go through the data.

Comparatively little room for “creativity”

As one of the volunteers involved in the clean-up operation, I think that one of the reasons for the high accuracy rate was that the project was very focused and didn’t leave the volunteers a lot of room to be “creative”. USAID asked us to do something very specific and gave us a tool that only allowed us to operate within very restrictive parameters: during the exercise, each volunteer requested five or ten datasets that were shown in a mask where he could only add the requested information. This left very little room for potential destructive errors by the users. If USAID had done this through a Google Spreadsheet instead, I’m sure the accuracy would have been lower.

My takeaway from this is that crowdsourced tasks have to be as narrow as possible and need to use tools that help maintain data integrity.

Walk, crawl, run

Prior to the project launch, USAID ran incrementally larger tests that allowed them to improve the workflow, the instructions (yes, you need to test your instructions!) and the application itself.

Tech support!

If you ask people in 24 time zones to contribute to a project, you also need to have 24 hour tech support. It is very frustrating for volunteers if they cannot participate because of technical glitches.

Volunteers in the Washington DC area could come to the USAID office to take part in the crowdsourcing project (Photo: Shadrock Roberts)

Volunteers in the Washington DC area could come to the USAID office to take part in the crowdsourcing project (Photo: Shadrock Roberts)It’s a social experience

This was emphasized a few times during the webcast and I think it’s an extremely important point: people volunteer their time and skills because they enjoy the experienceof working on a joint project together. That means you also have to nurture and create this feeling of belonging to a community. During the project duration, multiple Skype channels were run by volunteer managers where people could ask questions, exchange information or simply share their excitement.

In addition, USAID also invited volunteers from the Washington DC area to come to their office and work from there. All of this added to making the comparatively boring task of cleaning up data a fun, shared experience.

You need time, project managers and a communications plan

During the call USAID’s Shadrock Roberts said that he “couldn’t be happier” with the results, particularly since the costs of the whole project to the agency were “zero Dollars”. But he also emphasized that three staff members had to be dedicated full time to the project. So while USAID didn’t need a specific budget to run the project, it certainly wasn’t free.

To successfully complete a crowdsourcing project, many elements need to come together and you need a dedicated project manager to pull and hold it all together.

In addition to time needed to organize and refine the technical components of the project, you also need time to motivate people to join your project. USAID reached out to existing volunteer and tech communities, wrote blog post and generated a buzz about the project on social media – in a way they needed to execute a whole communications plan.

Case study and presentation

USAID published a very good case study on the project which can be downloaded here. It is a very practical document and should be read by anyone who intends to run a crowdsourced project.

In addition, here is the presentation from yesterday’s call:

PPT credit Shadrock Roberts/Stephanie Grosser - USAID

The entire case study was presented by Roberts, Grosser and Swartley at the Wilson Center 7/28. The event was livestreamed:

2 Comments

Great article! I’m always delighted when someone reflects on crowdsourced projects and finds common threads that lead to success. I wrote an article a few months back that outlines what I believe to be the three necessary components of a successful crowdsourced campaign, and you’ve hit on two of them: incentives and compartmentalization. Congrats on your insight!

Here’s the original article detailing what successful crowdsourcing entails:

I really enjoyed reading these reflections. While the volunteer coordinators did a wonderful job of relaying the thoughts of the volunteers, this sort of detailed look at the experience is invaluable for helping those of us who activate SBTF to continue improving.

I do want to clarify one detail: cost. As Timo rightfully points out, “USAID didn’t need a specific budget to run the project” which is why we say that it was “zero cost.” He also points to the fact that three of us were required to manage various aspects of the project so it wasn’t, in the purest sense, “free.” In actual fact, the three of us who managed the project put in an extraordinary amount of our own “volunteer time” to make the project go, since we took this on as an extra project in conjunction with our regular duties. We could make the argument that this constitutes “free” that would be missing the point.

What we want development and humanitarian agencies to understand is that the power of groups like SBTF is free in that these groups volunteer valuable resources, time, and skills: they want to help. However, this should not be viewed as a “free labor” but rather as a valuable resource worth investing in. It is for that reason that we have made a point of recommending that organizations create positions or build the capacity necessary to manage reach-back to the “crowd” and VTCs.

In the current fiscal climate, doing more intelligent development for less money is an imperative (I would argue that it should always be) so we wanted to communicate how cost-efficient this is. However, we don’t want to give the impression that projects like this are a magic box. Put rather simply, crowdsourcing is a long term project that needs clear goals, relationship building, and management just like any other. Rather than viewing this as free or not free, I’d prefer to think of it as a wise and incredibly high-yield investment.

Once again, thanks for the great post.