Cross-posted from iRevolution

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) activated the Digital Humanitarian Network (DHN) on December 5th at 3pm Geneva time (9am New York). The activation request? To collect all relevant tweets about Typhoon Pablo posted on December 4th and 5th; identify pictures and videos of damage/flooding shared in those tweets; geo-locate, time-stamp and categorize this content. The UN requested that this database be shared with them by 5am Geneva time the following day. As per DHN protocol, the activation request was reviewed within an hour. The UN was informed that the request had been granted and that the DHN was formally activated at 4pm Geneva.

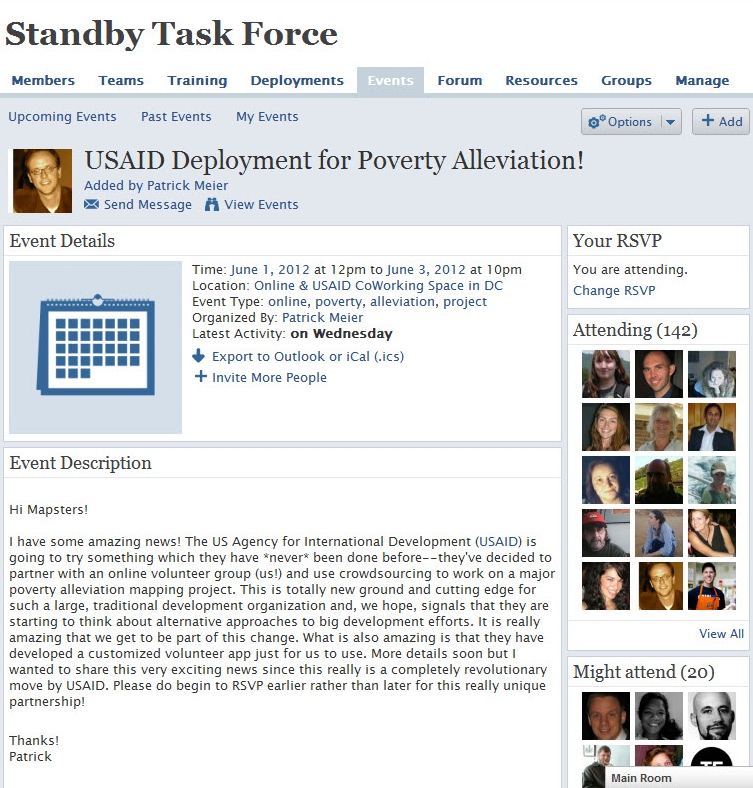

The DHN is composed of several members who form Solution Teams when the network is activated. The purpose of Digital Humanitarians is to support humanitarian organizations in their disaster response efforts around the world. Given the nature of the UN’s request, both the Standby Volunteer Task Force (SBTF) and Humanity Road (HR) joined the Solution Team. HR focused on analyzing all tweets posted December 4th while the SBTF worked on tweets posted December 5th. Over 20,000 tweets were analyzed. As HR will have a blog post describing their efforts shortly (please check here), I will focus on the SBTF.

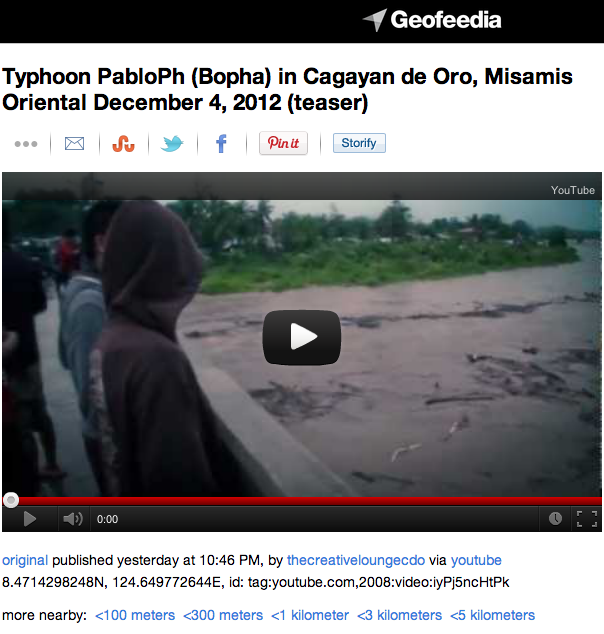

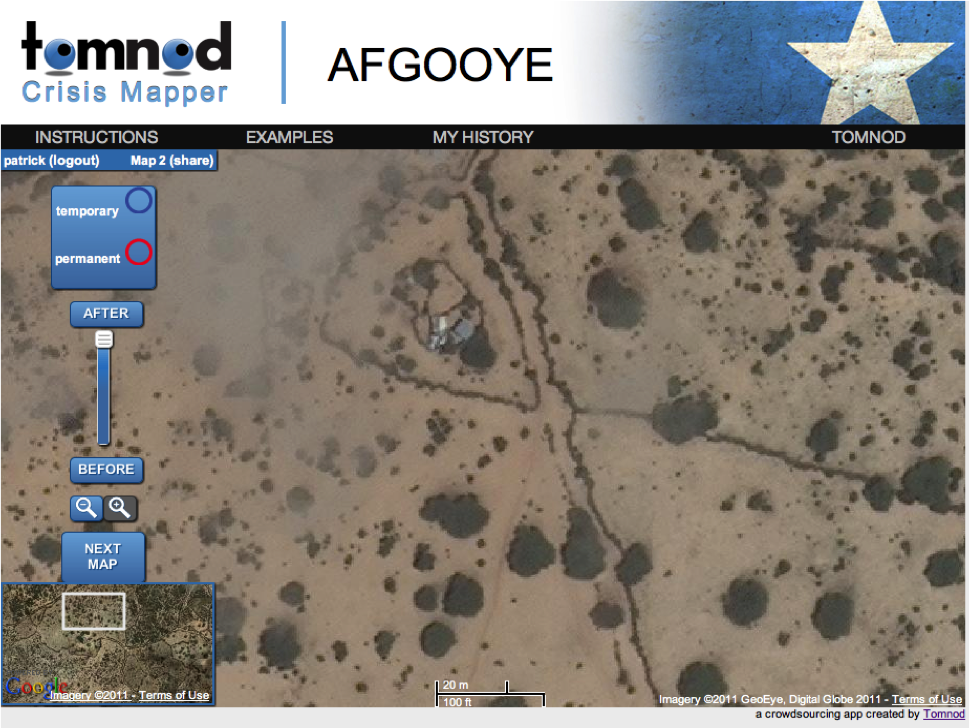

The Task Force first used Geofeedia to identify all relevant pictures/videos that were already geo-tagged by users. About a dozen were identified in this manner. Meanwhile, the SBTF partnered with the Qatar Foundation Computing Research Institute’s (QCRI) Crisis Computing Team to collect all tweets posted on December 5th with the hashtags endorsed by the Philippine Government. QCRI ran algorithms on the dataset to remove (1) all retweets and (2) all tweets without links (URLs). Given the very short turn-around time requested by the UN, the SBTF & QCRI Teams elected to take a two-pronged approach in the hopes that one, at least, would be successful.

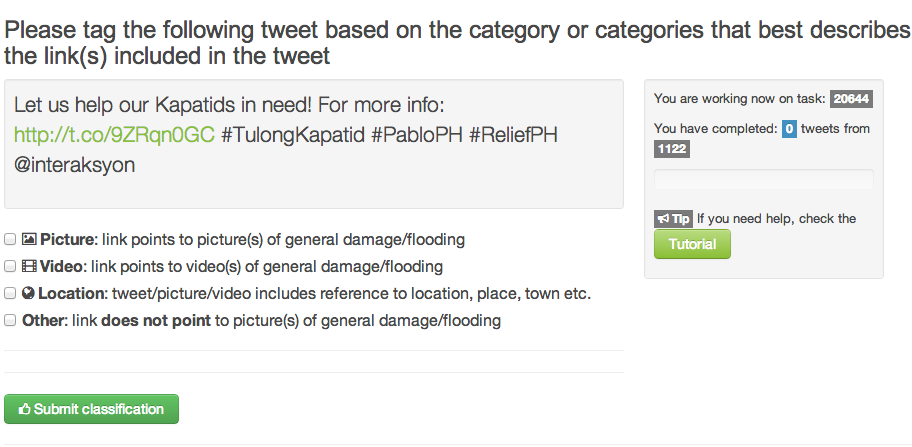

The first approach used Crowdflower (CF), introduced here. Workers on Crowd-flower were asked to check each Tweet’s URL and determine whether it linked to a picture or video. The purpose was to filter out URLs that linked to news articles. CF workers were also asked to assess whether the tweets (or pictures/videos) provided sufficient geographic information for them to be mapped. This methodology worked for about 2/3 of all the tweets in the database. A review of lessons learned and how to use Crowdflower for disaster response will be posted in the future.

The second approach was made possible thanks to a partnership with PyBossa, a free, open-source crowdsourcing and micro-tasking platform. This effort is described here in more detail. While we are still reviewing the results of this approach, we expect that this tool will become the standard for future activations of the Digital Humanitarian Network. I will thus continue working closely with the PyBossa team to set up a standby PyBossa platform ready-for-use at a moment’s notice so that Digital Humanitarians can be fully prepared for the next activation.

Now for the results of the activation. Within 10 hours, over 20,000 tweets were analyzed using a mix of methodologies. By 4.30am Geneva time, the combined efforts of HR and the SBTF resulted in a database of 138 highly annotated tweets. The following meta-data was collected for each tweet:

- Media Type (Photo or Video)

- Type of Damage (e.g., large-scale housing damage)

- Analysis of Damage (e.g., 5 houses flooded, 1 damaged roof)

- GPS coordinates (latitude/longitude)

- Province

- Region

- Date

- Link to Photo or Video

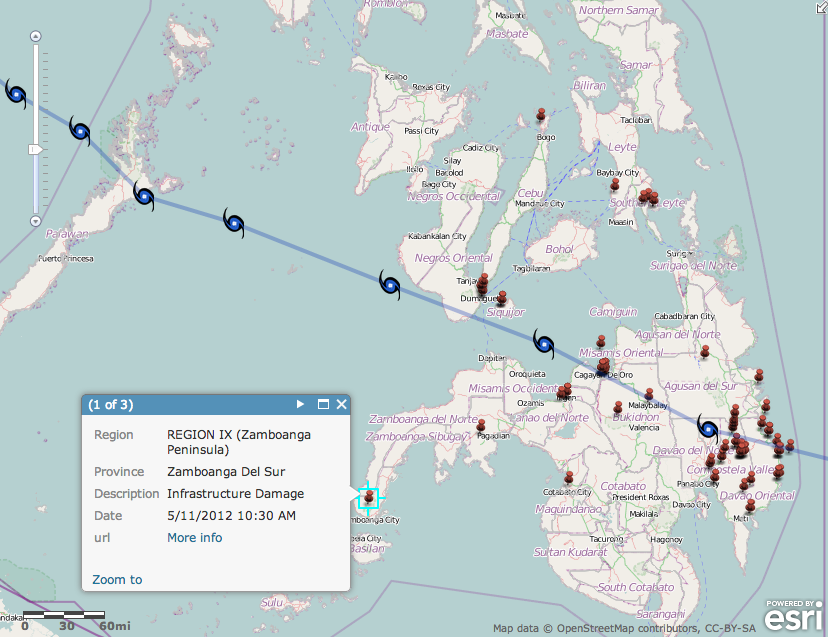

The vast majority of curated tweets had latitude and longitude coordinates. One SBTF volunteer (“Mapster”) created this map below to plot the data collected. Another Mapster created a similar map, which is available here.

The completed database was shared with UN OCHA at 4.55am Geneva time. Our humanitarian colleagues are now in the process of analyzing the data collected and writing up a final report, which they will share with OCHA Philippines today by 5pm Geneva time.

Needless to say, we all learned a lot thanks to the deployment of the Digital Humanitarian Network in the Philippines. This was the first time we were activated to carry out a task of this type. We are now actively reviewing our combined efforts with the concerted aim of streamlining our workflows and methodologies to make this type effort far easier and quicker to complete in the future. If you have suggestions and/or technologies that could facilitate this kind of digital humanitarian work, then please do get in touch either by posting your ideas in the comments section below or by sending me an email.

Lastly, but definitely most importantly, a big HUGE thanks to everyone who volunteered their time to support the UN’s disaster response efforts in the Philippines at such short notice! We want to publicly recognize everyone who came to the rescue, so here’s a list of volunteers who contributed their time (more to be added!). Without you, there would be no database to share with the UN, no learning, no innovating and no demonstration that digital volunteers can and do make a difference. Thank you for caring. Thank you for daring.

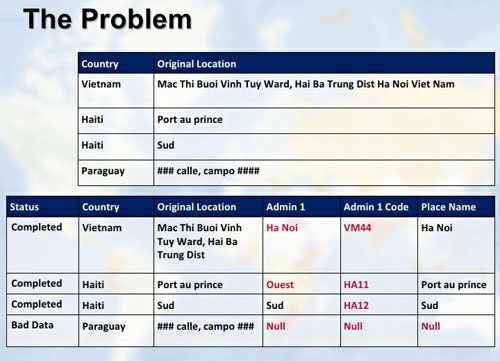

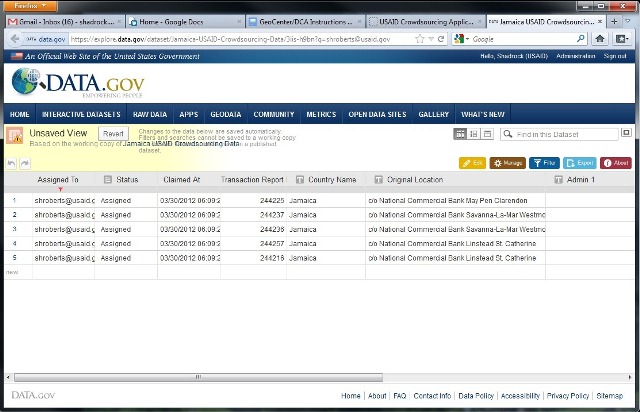

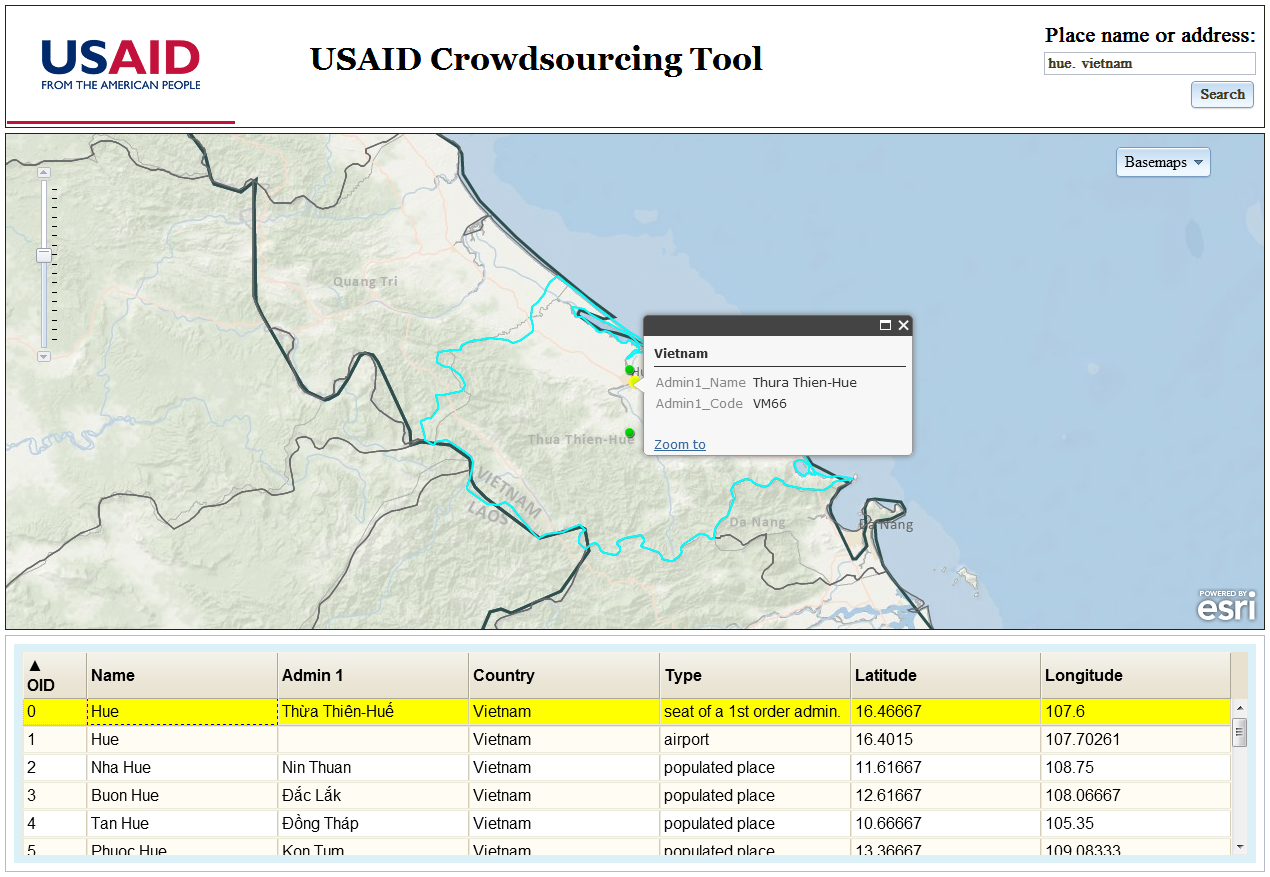

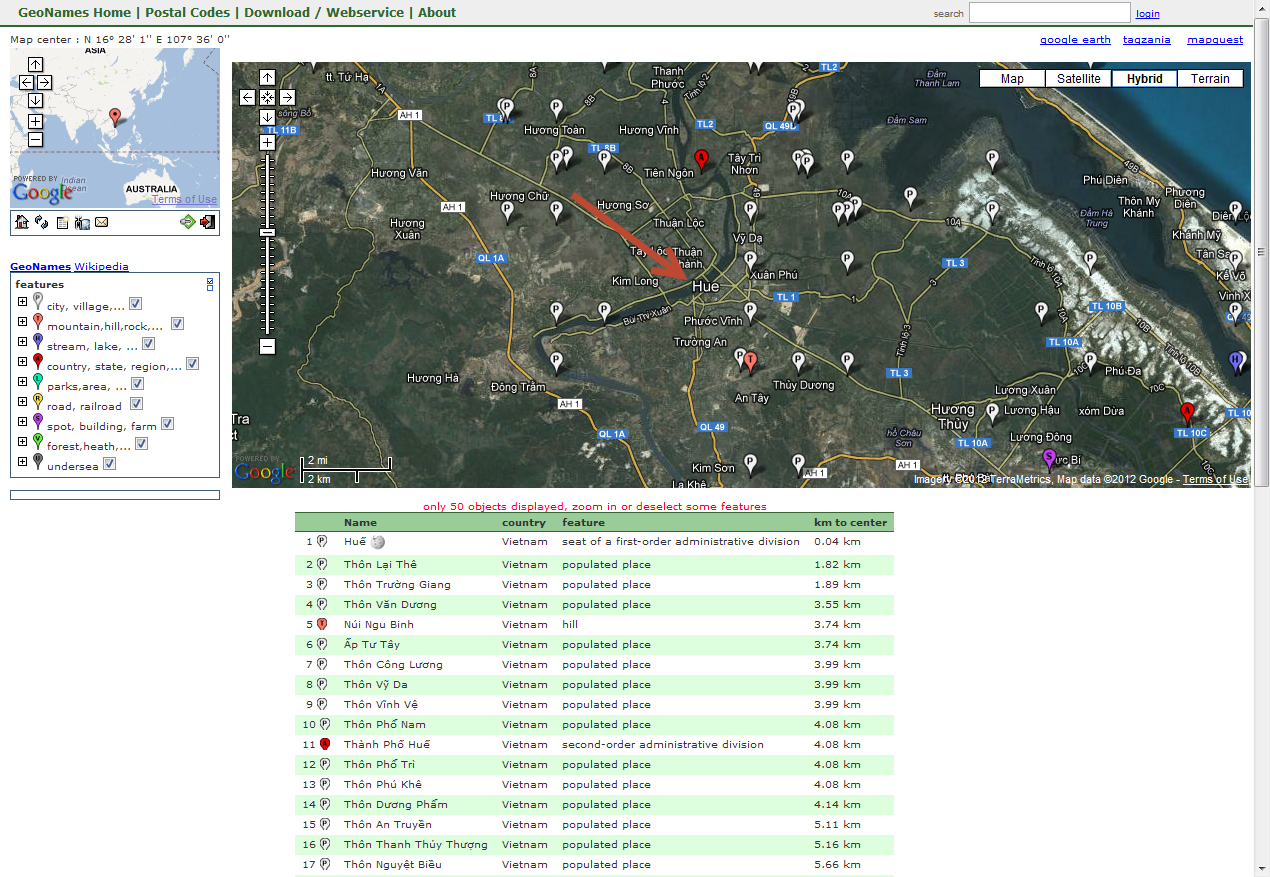

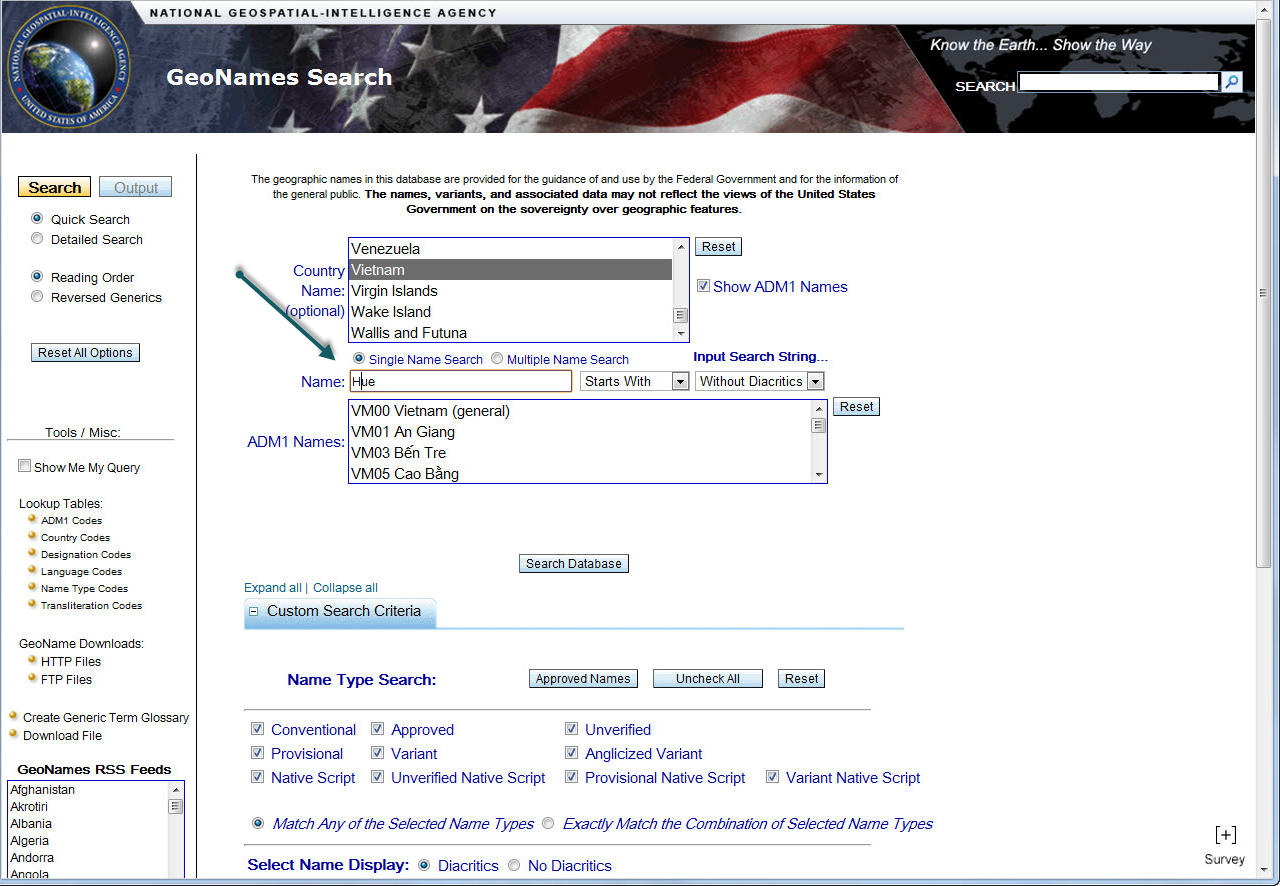

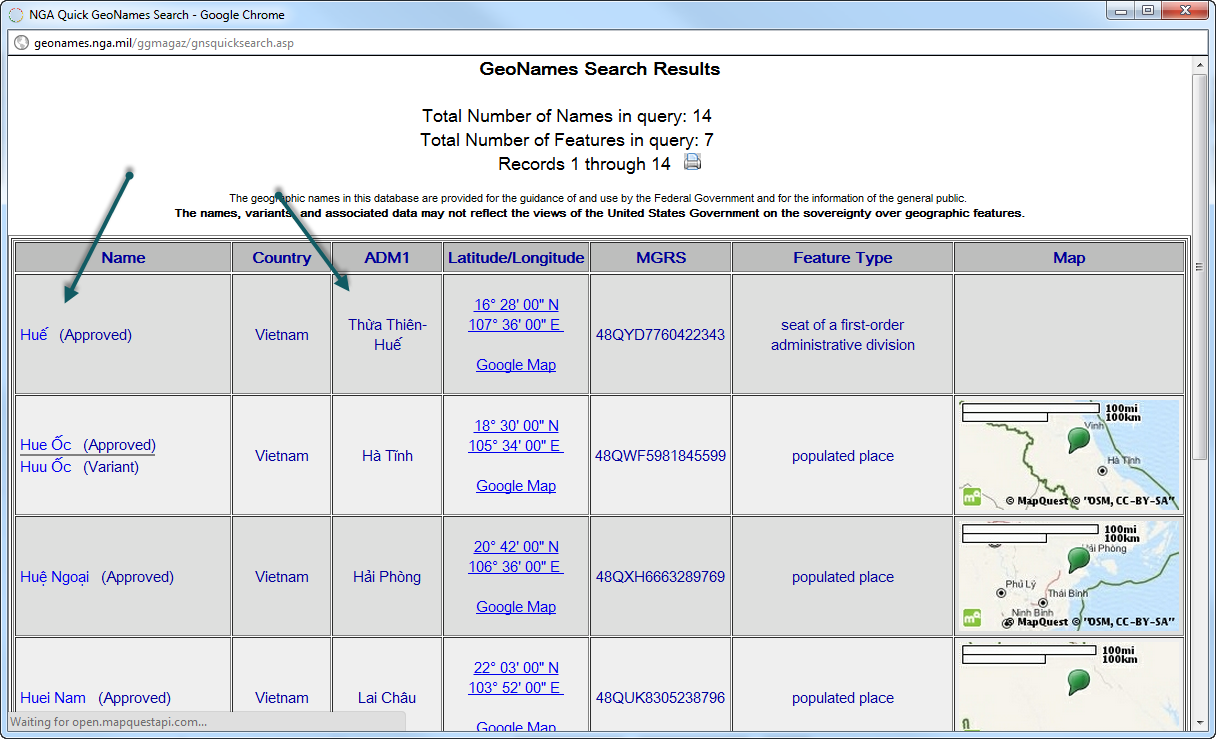

USAID/ESRI Lookup Tool:

USAID/ESRI Lookup Tool:

How the UN Used Social Media in Response to Typhoon Pablo (Updated)

Cross-posted from iRevolution.

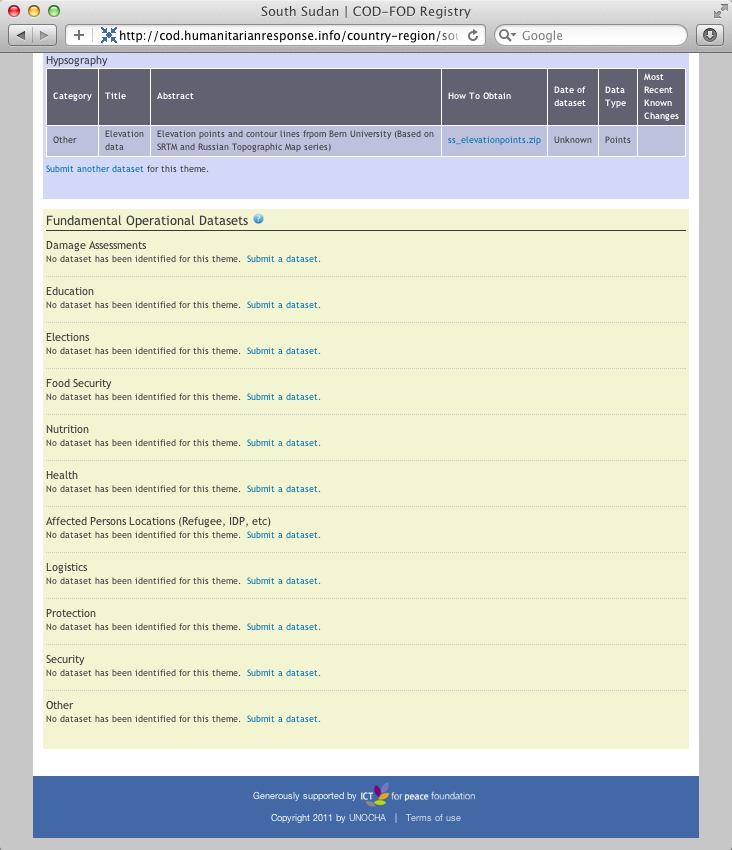

Our mission as digital humanitarians was to deliver a detailed dataset of pictures and videos (posted on Twitter) which depict damage and flooding following the Typhoon. An overview of this digital response is available here. The task of our United Nations colleagues at the Office of the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), was to rapidly consolidate and analyze our data to compile a customized Situation Report for OCHA’s team in the Philippines. The maps, charts and figures below are taken from this official report (click to enlarge).

This map is the first ever official UN crisis map entirely based on data collected from social media. Note the “Map data sources” at the bottom left of the map: “The Digital Humanitarian Network’s Solution Team: Standby Volunteer Task Force (SBTF) and Humanity Road (HR).” In addition to several UN agencies, the government of the Philippines has also made use of this information.

The cleaned data was subsequently added to this Google Map and also made public on the official Google Crisis Map of the Philippines.

One of my main priorities now is to make sure we do a far better job at leveraging advanced computing and microtasking platforms so that we are better prepared the next time we’re asked to repeat this kind of deployment. On the advanced computing side, it should be perfectly feasible to develop an automated way to crawl twitter and identify links to images and videos. My colleagues at QCRI are already looking into this. As for microtasking, I am collaborating with PyBossa and Crowdflower to ensure that we have highly customizable platforms on stand-by so we can immediately upload the results of QCRI’s algorithms. In sum, we have got to move beyond simple crowdsourcing and adopt more agile micro-tasking and social computing platforms as both are far more scalable.

In the meantime, a big big thanks once again to all our digital volunteers who made this entire effort possible and highly insightful.